In researching the USS Connecticut of 1799-1808, I was trying to collect as much data about details of the vessel and what might distinguish her from other vessels. One of the features common to warships at this time was the vessel’s figurehead, which would vary from vessel to vessel and often reflected perhaps the name of the vessel or a visual representation of something of the American ideal such as an eagle or statue of Columbia – a typically female motif that was one of many metaphors for the United States in the early decades. Visitors to Mystic Seaport can view a collection of such surviving figureheads from merchant and whaling vessels of men, women, children, mermaids, warriors, &c. In a letter from Seth Overton – Contractor for the building of the ship Connecticut – to a Noah Talcott, merchant, in NY (City), of 3 April 1799, there is some back and forth regarding a figurehead FOR the Connecticut; perhaps supplied by a Seth Wetmore as “the one in the store in Middletown (CT) it is unmountable (not the right size or unacceptable)”… But in the end, the figurehead used is not described.

After the conclusion of the “Quasi-War”, Congress moved on a “Peace Establishment Act” in which the navy was dramatically downsized. Vessels kept in service were in part due to perceived future service but politics played a large role, pushing otherwise very serviceable vessels into “mothballs” or simply put up for auction and sold. The Connecticut was one that suffered the last fate and on 9 May 1801, the USS Connecticut was sold to a NYC merchant Jordan Wright for 19,300$. When the vessel – now the privately owned merchant vessel Connecticut – was entered into the books at this point, it provides us the actual dimensions of the vessel (which differ a bit from the proposed dimensions before building commenced and is what is cited as the vessel’s proportions in US Navy description and subsequent citations by those who touch briefly on the vessel), and specifically states that she has a “Man Figurehead”.

So my curiosity piqued, I set out to find just what “man” might have been the figurehead for this ship. After years of digging, I found nothing, and settled upon the idea of perhaps a clue might be in the name of the ship and the river…

In researching shipping along the Connecticut River for the biography of Moses Tryon, I learned that while most rivers around the world are thought of as “female”, there are some considered “male”, such as the Mississippi (think the song “Old Man River”). Well, it appears that the Connecticut River is ALSO considered “male”, such as in the article in the Middlesex Gazette on the launching of the ship Connecticut: No words can convey an adequate idea of the beauty and brilliancy of the scene. Nature, as inclined to do honor to the occasion, had furnished one of the most delightful days that the vernal season ever witnessed – while Old Father Connecticut, eager to receive his beautiful offspring, had swollen his waters by the liquefaction of snows reserved for the occasion near his source, in order to facilitate her passage to his wave; and extending his liquid arms, welcomed her to his embrace.

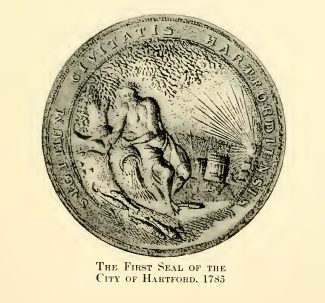

So while doing this I came across a copy of The Colonial History of Hartford by the Rev. William DeLoss Love, Ph.D., published in 1914. In chapter 11, it is stated, “… in 1785, Colonel Samuel Wyllys, alderman, and John Trumbull, Esq., councilman, reported a device for the seal of the newly incorporated city… Thus it happened that the above committee reported as follows: Connecticut River, represented by the figure of an Old man crowned with Rushes, seated against a Rock, holding an Urn, with a Stream flowing from it; at his feet a net, and fish peculiar to the River lying by it, with Barrels and Bales; over his head an Oak growing out of a Cleft in the Rock, and round the whole these words, “Sigillum Civitatis Hartfordiensis”.

The seal is below:

With all this, I feel comfortable with the conclusion that the figurehead might very have been some representation of “Old Man Connecticut”, and until I find any evidence to say otherwise, I’ll leave it at that.

Jos. Morneault