This Page Is Under Construction And May Be Frequently Updated

I know that this is a little bit off topic, but in collecting things that someone from this era might have carried, I found myself on a side journey; I think it noteworthy to share here. This has been an intriguing project and I know that while I’ve hit a few walls in the research, only to uncover a key to a door I was stuck at, there might be more focused genealogists who will take what I have here and expand it (and maybe even correct some of it). At least I will have answered some questions and then provided a launching pad for someone’s greater project. I live in Connecticut, USA, and as I commonly travel to the locations regarding my research – when I am able – not having Basingstoke within a couple of hours drive leaves me with doing my research entirely by the internet and by tapping into the help provided by others. I accept full responsibility for my conclusions below; should you have questions, anything to add, or to critique, feel free to reach out either as a question posted on this webpage or directly to my email address: JosMorn@aol.com

Joseph Morneault

- My Motivation

- The Purchase

- Questions and the Search Begins

- Some of the Evidence

- The Search for James Gregory

- James and his Will

- William Gregory

- Silversmith – Watch Case Maker

- Conclusion

- The Gregory Watchmakers in Basingstoke – PDF

My Motivation

When I was about 8, I was staying over at my grandparents’ place then in Meriden, CT (before they returned to New Brunswick, Canada). Although it was in a warm month, somehow the topic came up about Père Noël and I asked mon pepère “How can he visit EVERY house to deliver presents around the world and get it done in one night?” Pepère went into the other room and returned carrying a pocket watch (from his retirement, perhaps?) and showed it to me, having me listen to the ticking as he held it to my ear. “Père Noël has a pocket watch that can stop time. Right at minuit, he stops time, then goes all over the world to deliver the presents. When he is done, he starts time again for everyone. This is why you never see him placing the presents under the tree!”

Although I was nigh on putting such lovely children’s myths behind me, I held that tale close to my heart. This caused a fascination with pocket watches for me ever since. Then, right about when I turned 13, the movie came out with Pam Dawber and Robert Hays entitled “The Girl, The Gold Watch, and Everything“. This reignited the myth in my mind, and I really wanted a pocket watch of my own! A few elders along my street had their own and has shown me theirs, but it was this movie that added the necessary fuel.

As a budding historian in my teens, I did purchase a 50$ pocket watch from a local jeweler, but it died in a couple of months; even changing the battery did not help. I found that pretty much anywhere one would go to pick up a watch would sell high end wrist watches but cheap pocket watches with some sort of non-descript metal or maybe even aluminum, with a gold wash that rubbed off while in the pocket, and didn’t even have the reliability of a Timex. “You want a GOOD pocket watch? Go into the city but be prepared to spend a lot of money, kid!” When I was 19, I purchased a 200$ Aero pocket watch while on a visit to Basel, Switzerland; a “hunter style”, with the hinged cover. I still have that one and I consider it to be my “first” pocket watch for it was the very first one I owned of more quality than something one might win from a claw game machine. Not high-end by any means, but reasonably reliable. As I got involved with late 18th century ceremonial and reenactment groups, the urge to have an original watch from the era that works became the evolution of that desire. I would find older friends “in the hobby” sporting their 18th century original watches or replicas, and when I asked where they obtained it, the answer was almost always “I picked it up on my trip to London” or some variation. A key-wound watch I purchased from an antique store didn’t work beyond 5 minutes… nickle case. I brought it to a watch repairman here in Connecticut who refused to work on it as he declared that it is a “Swiss Fake”; working on it would “ruin his reputation”. By this time I had been a craftsman of flutes, fife, flageolets for some 30 years, and I explained that copies of historical flutes are still flutes; we still service them, with the scandal of supporting makers that replicate being long gone with their deaths some 100 years ago. Nonetheless… So, commenting about this to my elderly employer, he shared with me that his brother John had gone to school specifically to make watches from scracth, and not merely service them!

Off to see “Uncle John”, he brought me up into his upper floor workshop. Lots of watches and cylinder records, which he also collected. He told me that a particular balance stem was broken and that he would have to make a new one; one cannot simply call for replacement parts on this 1879 watch! Yes, made by someone in Switzerland to resemble a Waltham watch, but still a decent watch!

A ‘phone call a week later and he said to bring 50$ and pick my watch up! We discussed my “bucket list wish”, and he said that he had a watch to show me! It had belonged to his great grandfather (or perhaps the father before – I forget) and that he inherited it… I told John that I was reluctant to see it for I might want it! He smiled, whistled a little tune, and pulled a shoe box out of his closet. Despite my continued protestations, he opened the lid, parted the jeweler’s wool, and produced this absolutely lovely silver watch! Paired, and when the outer case removed, a pastoral scene with nude sprites were painted on some material and tucked into the back of this outer case. The watch ticked happily when John wound it, and I think that I might have actually salivated! “I’m pretty old, and there’s no one in the family who cares about this or any of my watches. Remind me about this in a few years and if nothing changes, I’ll give you this watch”. Wow! What a promise!

Some years later, John was slipping into early dementia. I had visited him again many times over the years and he did all the servicing to my growing watch collection – I had picked up another from 1886. I gave him my 1879 as he actually wanted it. But this time, it was strictly a social call. Sitting at the kitchen table, his wife on the other end, John said that he knew that he was “slipping”, and would like to give me something to remember him by. I felt a little odd asking, but I mentioned the watch. He genuinely looked puzzled, seemed to rack his brain, but couldn’t recall such a watch. His wife could but couldn’t go up the stairs anymore. I simply dropped the topic… It felt too much like taking advantage. But now I was determined to find my own watch from “my era”.

The Purchase

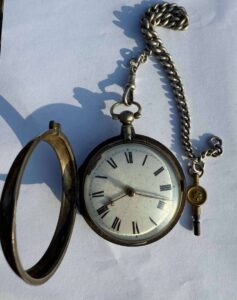

In February 2025, I made the purchase of an antique verge fuzee watch, a “paired” one, from a seller in the UK. To have a working pocket watch from “my” era (1790 – 1810) has been on the top of my “bucket list” since about 1990, and this was most exciting for me! I tried for one dated ostensibly to 1805, but while I “won” that auction, it didn’t meet the seller’s reserve price, whatever that was supposed to be. I played the game a second time, won again, and still didn’t meet the hidden reserve price. I made a direct offer which was turned down, and so I moved on to another lovely, silver pocket watch that was dated to 1816. Of course, this is much later than “my era” of the 1790s-18-aughts range, but this seller stated that it was working although in need of some TLC. I won this auction and the seller sent it along.

It is rather irrational, I suppose, to hold something in your hand for the first time (children and the newborn of your pets exempted) and feel an immediate connection. Yet there I was, in love with a watch and was glad for it! It seemed in that first moment of holding it that this was the longed-for moment of everything leading up, per my back story above. It did not come with a key (for these are key-wound), but I have a set of watch keys of different gauges, and I quickly found that it wound (anti-clockwise) and worked; that said, it could lose 10 minutes, or gain an hour, seemingly at random. I have a contact in Maine who did, to my mind, miracles in restoring my step-father’s family clock (believed by family tradition to date to 1782/4), and did wonderous restoration to another of my pocket watch collection (post-Uncle John). So, I shipped this, reluctant to send it away, in the post. A few weeks later, I was going up to the family farmhouse, and I reached out… We met and my man placed it back in my hand, telling me that this type of works for a pocket watch is out of his area of comfort and would rather I take it to someone keenly focused on this style. (A verge fusee requires more of an artist watch repairman and he is more of a later-works technician) I honour him for his honesty, and I brought it away with me. An internet research for who might be a good candidate turned up someone in New Hampshire, but with a waiting list. A recommendation was passed along to reach out to Nathan Das of Hallicra’s Works in Canada. I sent it along to Nathan and he did a fantastic job with it! I highly recommend him!

Questions and the Search Begins

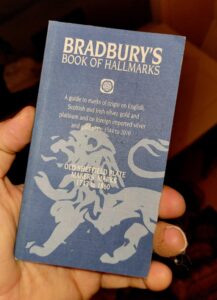

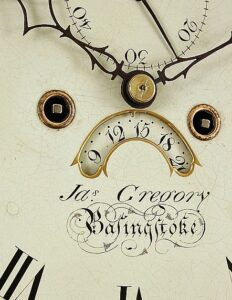

Meanwhile, I joined a couple of Facebook groups related to antique pocket watches. I had a lot to learn and while my dear ol’ friend Steven could answer many for me, there were more still to understand. Being a research-historian, I simply had to learn as much as I could about the maker. I posted photos of my watch and told a thumbnail of the story, and one of the members explained to me about dating by hallmarks, and that the date of the hallmark is not necessarily the date of the watch; at this time, it was more common that a dedicated silversmith would be the maker of the case for the watch works made by the watch maker. So, as I do, I began a concerted search online for data to understand watches of the era and of hallmarks. The name of the watch maker is engraved on the back of the works – Jas. Gregory. I know of a few people from the 18th century whose names were Jason and used “Jas.”, but this turned up nothing of use. Quickly learning that it was more common for “James” to use that, my search opened up. James Gregory in Basingstoke, presumably England. What could I discover about him? Had I turned up someone else’s bio on the man, that would have been enough, and I would have moved on. But there’s scant little, and now my curiosity was piqued. I dug here and there, gleaning some very brief references to the man and his shop on Winchester St in Basingstoke, and that he also made case clocks and sold (or made?) musical instruments… this sounds familiar to the son-in-law to surgeon’s mate Dr. Nathan Tisdale… And Basingstoke immediately came to the mind of another friend who is a Jane Austen fan. For context, see this flyer from the Basingstoke Heritage Society. -> Jane Austen Leaflet

Some details of my watch…

‘Round about this time, Karen reached out to me via Facebook Messenger; she, also, had a Jas. Gregory watch by way of her grandfather, and asked if I had any information on the maker… See the following gallery.

- Jas. Gregory. Basingstoke. Serial number 570

- Per the Bradbury book, this silver would date to 1804

This was fuel to my fire, and while I shared with her what I had thus far collected, I needed to know more. I found a copy of Bradbury’s Book of Hallmarks (for a reasonable price… some of the ones I saw listed had insane price tags on them) and followed the “rabbit hole”…

- Note the right hand side, the red circle and the blue circle to correspond with my text.

Some of the Evidence

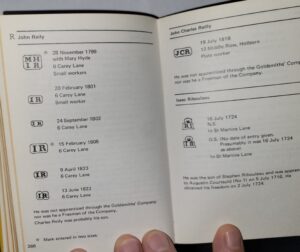

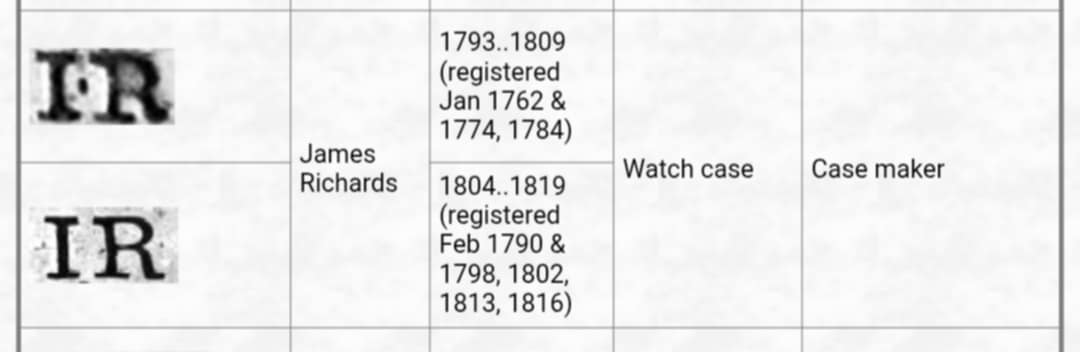

The hallmarks on the silver outer and inner cases for my watch have specific hallmarks. There’s a lion, a lion’s face with a crown on it, the letter “a” in lowercase (not the “g” an online friend thought that he could distinguish), the initials IR, and a small crescent. Looking at the Bradbury book, it would seem that the silver was brought to London to be assessed. The marks indicate that it was done by the London Silversmiths Office, given the lion and the lion’s face wearing a crown. Per the [a] it would seem that my watch had been made in 1816; yet shouldn’t it have an additional “duty mark”? I was to learn that this was not reliable, and more likely for watches expected to be exported. The letter is the indicator of date: they would start with a lowercase “a” and go up the alphabet until “u”, then move on to uppercase “A” until the end and start again… to this point, “a” would be 1776, “u” would be 1795, then “A” 1796, “U” 1815, then “a” again would be 1816. The initials are “IR” and there’s a journeyman’s mark in the form of a tiny crescent. Online I found a listing of known silversmiths and dates of the surviving examples, and my “IR” doesn’t fit any of those listed (The I is for J, thus it is really JR, and the only examples are variations of the initials in a rectangle and the dates don’t pin any of them to my watch). So, that’s another angle of research…

If you can make out the scratched numbers towards the top of this photo, these are “service marks”, or marks by a watch maker who serviced the piece for maintenance.

So, in order to learn fully about my watch, I need to track down Jas. Gregory AND whoever the silversmith “IR” stands for…

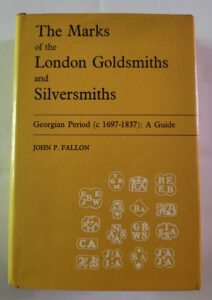

Here is another authoritative source for this work. Mr. Fallon is in agreement with the Bradbury book cited above. I’ll address this more in the Silversmith – Watch Case Maker section, but do look at the notes I’ve put with the images just below here.

- Note the encircled paragraph, explaining the Sovereign’s Head Duty Mark

- Within the rectangle, one sees the corresponding marks to my watch.

- Within THIS rectangle, it is clear to me that an 1816 date requires the addition of the Sovereign’s Head Duty Mark.

6 August 2025: I entered into conversation with Nathan Das of Hallicra’s Works in Ontario. He explained a few things to me that cleared up so many of my questions and put aside some speculation about the case works. “Just by looking at the movement and containing a slide regulator rather than a tompion regulator we are likely in the early part of the 19th century. There are other indicators too which will coincide with the later date. Sadly using the export duty mark (or lack there of) as an indicator of year isn’t enough as this is lacking on many watches especially if they were first sold inside of English territory.” So, despite the lack of duty mark AND the indication that the duty mark commences in 1784, it would appear that it wasn’t used for domestic sales of the watch (so, within Great Britain, and possibly the various colonies?). Understanding this alone is enough to slide all other indicators to the next time the lower case {a} is used, which is 1816. Knowing that “Gregory’s” was established in 1790, per the family shop assertions, the comparatively higher serial number engraved on the works, &c, &c, I think that Nathan’s input has been the final convincing puzzle piece for me. What’s more is that Nathan went on to say about the silver case… “Cases and movements are actually paired together. No surplus case would be made for a future date as the diameter of the movement would be unknown. In fact the movement, case, and sometimes back of the dial will all have the same serial number to keep together when watch portions were sent to silver smiths and dial makers. Each one custom fit together. No dial from one watch or case from one movement will fit another.” That would mean that the a theory I had about making cases en masse does not hold water! I am happy to have gained more light into this and am comfortable with how things are settling into place.

I have also learned that over the years, some people had removed the case of silver or gold and “liquidated” them for the cash value. Thus, there are watch works out there available without a case, or sometimes a watch would be fitted into a later case… I have since purchased such a watch that had been made in 1785 and had originally been in a gold case but later fitted into a silver case in 1850. This may have been to cash in the gold, or to have a more “fashionable” case at the time. Ah, if only things would stay simple!

You can see Nathan and his shop in the following vid:

If you are at all interested in seeing the works of a verge fusee watch, you might clink on THIS link to “The Naked Watchmaker“.

The Search for James Gregory.

– When I first made this page, it was a muddy step-by-step of my research and findings on James Gregory. Since then, I have made another page detailing all of the results for the Gregory Family of Watch Makers. I recommend that you read that for more information. I have been whittling down my previous ramblings within THIS specific page. –

As I have said earlier, an internet search yielded some clues, thankfully, for Jas. Gregory. The late Arthur Attwood, historian and publisher of “The Illustrated History of Basingstoke” was a good launch for me. By way of him and some odd documents I was able to glean off of Ancestry.com, I learned that James Gregory was indeed a watch maker, clock maker, and seller of musical instruments in Basingstoke, Hampshire, England. There’s a photograph of the family shop, taken in 1887, that shows an establishment date of 1790; see below. He does first appear in what local records I could find by the internet in 1790. He is cited as having worked as late as 1819 or so. I have not yet had any luck identifying who James would have apprenticed under. James’ shop appears to have been always on Winchester St… “one where the Johnson’s dry cleaners were until recently and before that on the other side of the street (north side) next to the entrance to Joice’s Yard.” So, the second location was on the south side, and Attwood indicates that Gregory was certainly at this 2d spot by 1819.

It is important to note that in Hampshire County and not too far afield, there are A LOT of Gregorys… John, James, Mary, William… There seems to have been little imagination or inclination for greater variation beyond tradition, and this makes genealogy in general a migraine in the making! Most of the genealogies I’ve seen are patchwork, incomplete, and only serve to throw more mud in the water, albeit with the best of intentions. In an effort to parse out a family line, I, too, started a tree on that site to take advantage of their search engine. The result has been that far too many of the suggestions for one person or another are pushed for the wrong person; something more likely for a father is being suggested for the son, but it won’t allow for reassigning to the father. Or a long line of baptismal records for the name and in far away counties, but when you toggle the location bar to Hampshire, it gives the result of “no result”… yet I found the baptismal record for James and siblings in Hampshire, so this is clearly a “researcher beware and be diligent” project. With a great deal of time and effort, and the internet along with joining myriad UK entities for access to records, I have made a family tree document separate from this blog entry. Some of the records available via Ancestry or Family Search here in the US are bad copies (muddy or dark or faint), or tantalizing in that they cite the existence of the document, but one must either travel to an official LDS site to view what is otherwise public domain documentation, or it is cited as being “in the vault” and not accessible for the public. These are cases that I fully believe are either meant to wring a little more money out of the inquiring scholar or simply held to create a sense of a power-structure… “Need to know basis and you don’t need to know”. So, I’m doing my best to leave something for Gregory descendants and Basingstoke historians to use as a viable launching pad.

In communication with Debbie Reavell of the Basingstoke Heritage Society, the north side of Winchester St location was The Crown Inn entrance surviving as Joice’s Yard. The current business there is The Money Shop. There is a photo of the Gregory shop taken for the 1887 Golden Jubilee. See the images old and recent below…

- Gregory’s shop on Winchester St, apparently taken at the time of the 1887 Jubilee of Queen Victoria

- The same building today – 2025

My document on the Gregory Family of Watchmakers. Gregory Watchmakers in Basingstoke^J England

According to the 1790 “Universal British Directory of Trade, Commerce, and Manufacture“, vol. 2, p.317 (Hampshire extracts), available via Ancestry.com, James Gregory is listed as “watch maker” in Basingstoke, Hampshire, England: This is the earliest I can find of the man as a watchmaker. Elsewhere he is also listed as a “clock maker, and (seller of) musical instruments”. The 1792 edition of this directory also lists him as a “watchmaker”. Still another source claims that he was working from 1790 through 1813, and another that he was still in business in 1819.

There are other James and William Gregorys in Basingstoke and the surrounding area… a lawyer, a farmer, a policeman, a common labourer… Again, be careful with what Ancestry search results you are handed! I will note that I wholly agree with Ms. Reavell that our James Gregory had not married, given James’ will and how the business moved in the family.

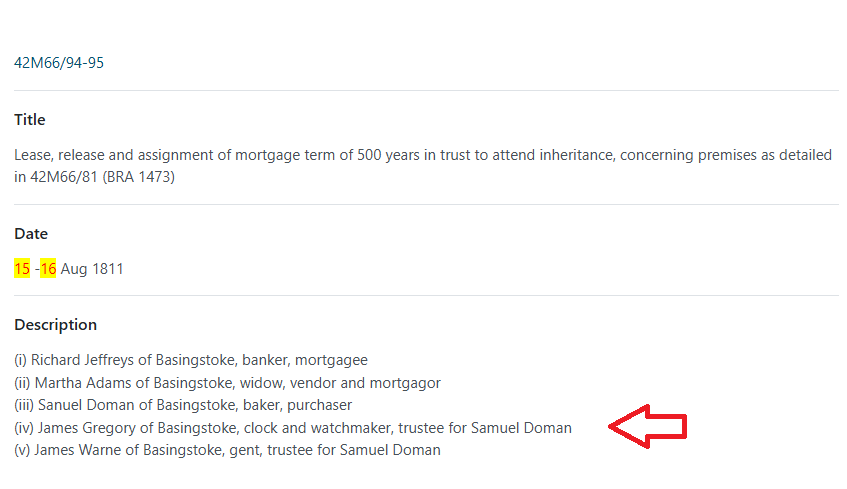

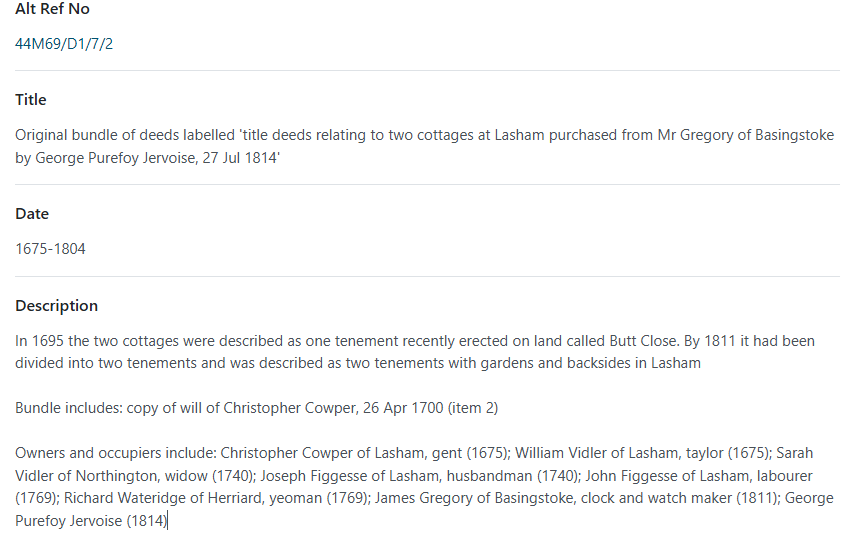

Here is a land record provided by Ms. Reavell, mentioning James in 1811, and his occupation. Note that he indeed listed as a watchmaker and not a vendor or shopkeeper. During my quest on the silver case, someone “in the field” had confidently assured me that, not ever having heard of James Gregory, Mr. Gregory had his name engraved on the watch as either the vendor selling a watch made by someone in London (advertisement), or the owner of said watch. By the time you reach this document and the Gregory Family page, I trust that you will also agree that the evidence points to James Gregory having been an actual maker of watches and clocks…

Also the mention below:

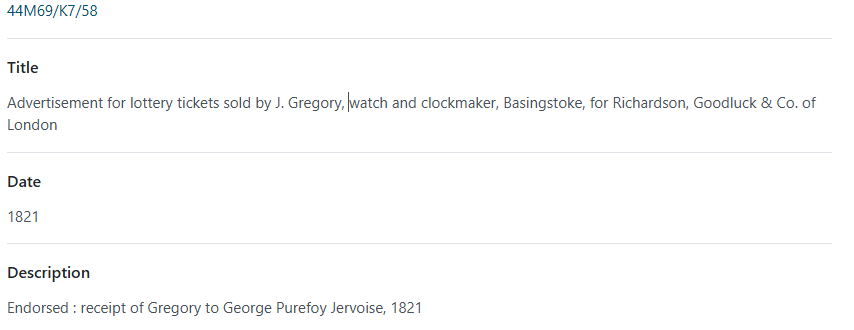

Another note regarding the shop of James Gregory selling more than only his watches and clocks – ie: musical instruments and lottery tickets. We tend to think of early tradesmen (particularly those not immediately affected by the industrial revolution) only doing that specific trade, while today we see storefronts of craftsmen also dealing in seemingly unrelated retail items. I put this thought to a couple of historian friends here in Connecticut and in New York, and the response was interesting. It would seem that there are myriad examples of watch and clockmakers here in the US during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, where musical instruments were also for sale. For example, If one were to look at the son-in-law to Nathan Tisdale, Roswell Walstein Roath watchmaker and jeweler in Norwich, Connecticut, for instance, that is exactly the business model he engaged in, (made watches, cast silver into spoons and jewelry, set stones in his jewelry, sold musical instruments, and even tickets for local lotteries, likely cast and made his own watch cases), and continued to do so when he removed his family to Denver. It was almost considered a standard in New York City for clockmakers and watchmakers to have a storefront that ALSO offered musical instruments and sometimes other items to sell as supplemental revenue, such as the aforementioned lottery tickets. So, Gregory selling musical instruments would not be a singular circumstance.

To further the point on James making clocks, The Hampshire Cultural Trust has a case clock listed as having been made by James Gregory. And there are a few more examples of his clocks that I have found photos of…

- A tall case clock by James Gregory. Sold by P A Oxley Antique Clocks & Barometers Images found at https://www.sellingantiques.co.uk/132472/small-oak-longcase-clock-by-gregory-of-basingstoke

- Small oak tall case clock by James Gregory, Basingstoke. Sold from P.A. Oxley, Quality British Antique Clocks & Barometers. https://british-antiqueclocks.com/archive/225-small-oak-antique-grandfather-clock-by-gregory-of-basingstoke.html

- Small oak tall case clock by James Gregory, Basingstoke. Sold from P.A. Oxley, Quality British Antique Clocks & Barometers. https://british-antiqueclocks.com/archive/225-small-oak-antique-grandfather-clock-by-gregory-of-basingstoke.html

- Small oak tall case clock by James Gregory, Basingstoke. Sold from P.A. Oxley, Quality British Antique Clocks & Barometers. https://british-antiqueclocks.com/archive/225-small-oak-antique-grandfather-clock-by-gregory-of-basingstoke.html

Maps below to indicate where in England one would find Basingstoke, for those who are not local to South Central England.

James and his Will

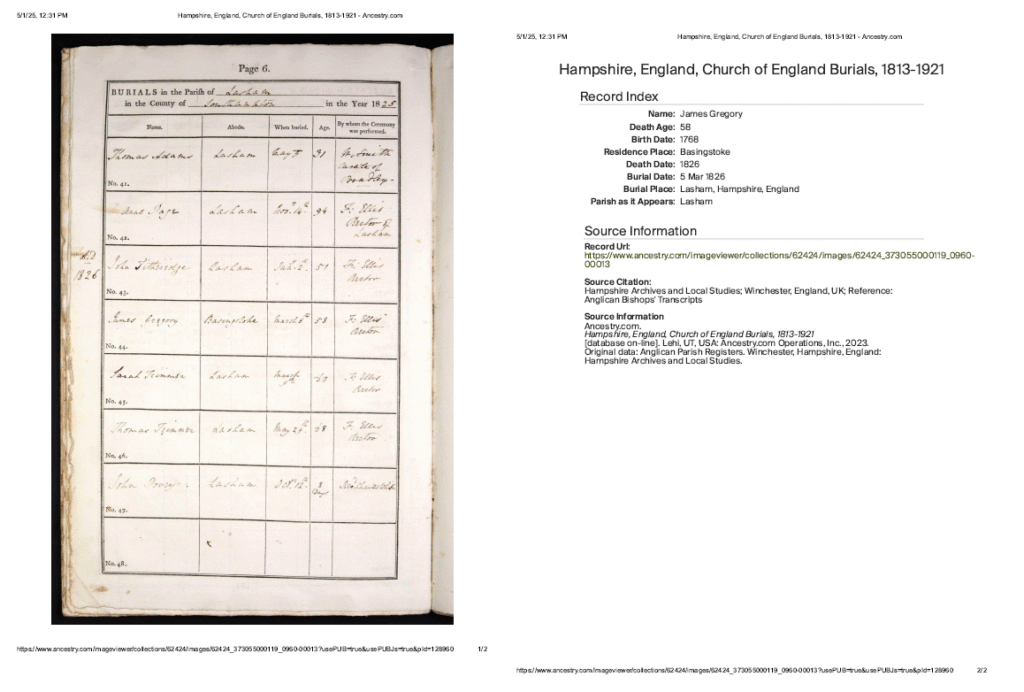

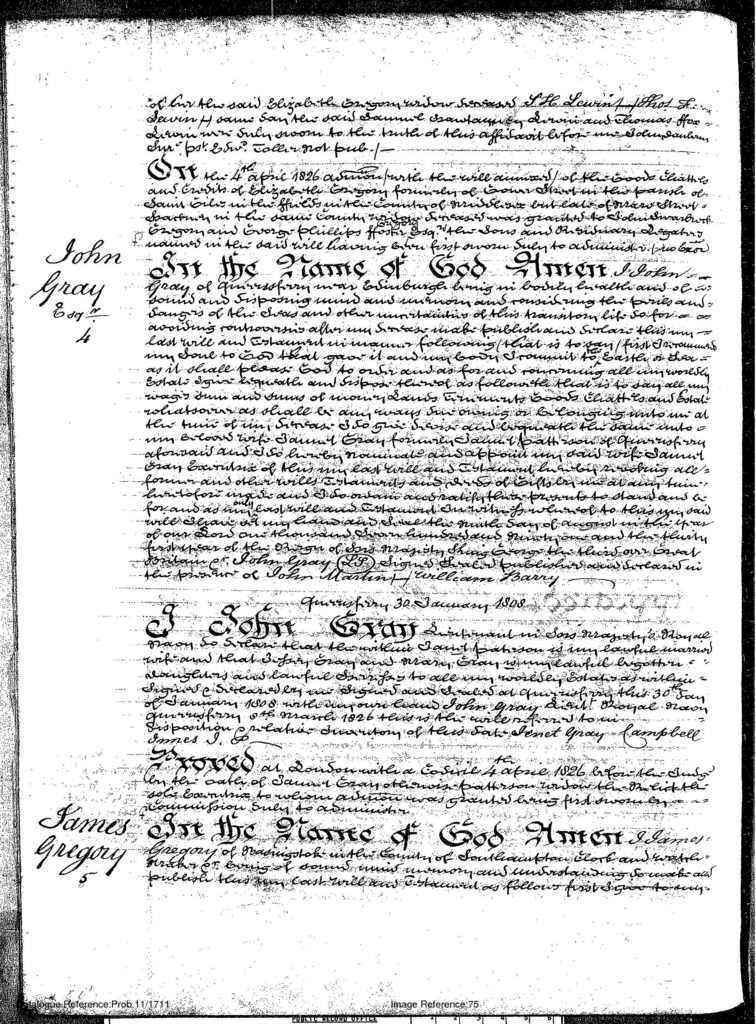

The Hampshire, England, Church of England Burials, 1813-1921, via Ancestry.com, indicates that James Gregory died in Basingstoke on 5 March 1826, aged 58. If this is correct, and we know that sometimes the age recorded at death is inaccurate, this would give 1768 as James’ birth year. In his will, I have been informed, James left the business to his nephew William; and that he also asked to be buried near his father John Gregory in the Lasham churchyard, which is adjacent to St-Mary’s Church and not very far from Basingstoke. That will is digitized and available via Ancestry, but the image is muddy and difficult to parse out. I reached out to a couple of friends who are stellar in this work: Donna and Thomas, and they happily took up the challenge… and it became the Rosetta Stone for this quest.

For citation source, it is “Will of James Gregory, Clock and Watch Maker of Basingstoke, Hampshire.” Reference: PROB 11/1711/62

Date 05 April 1826

Held at the National Archives, Kew, Richmond, England.

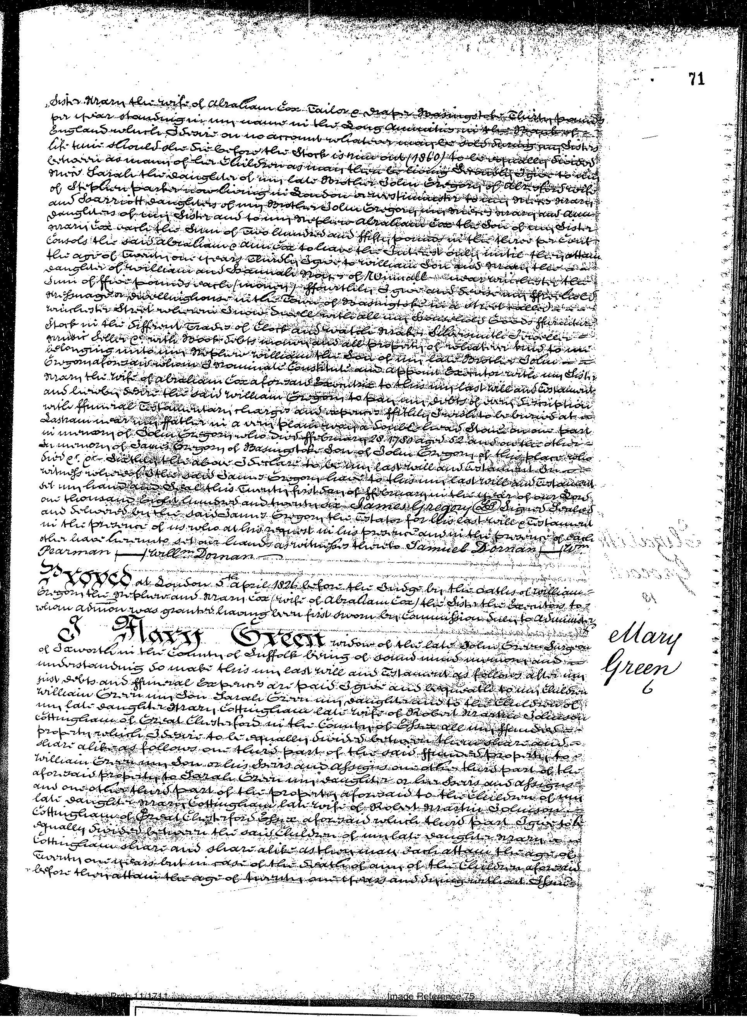

What I now have is a family set: It would seem that James never married, nor had any offspring acknowledged in his will. “I James Gregory of Basingstoke within the County of Southampton, clock and watch maker, &c, &c.” He cites his living sister Mary, wife of Abraham Cox in Basingstoke, a tailor and draper by trade; their children Mary, Ann, and Abraham, the latter two being under the age of 21 in 1824. James refers to his brother John, deceased by the time the will is drawn up in 1824, and John’s children: Sarah (wife of Stephen Parker of London), and William. William is to be one of the two executors (along with Mary Cox, James’ sister), and William will get the house, shop, and business. James wished to be buried next to his father John Gregory, who died 28 Feb 1780 in Lasham.

This will was “proved before the judge” by the oath of “William Gregory, the nephew and residuary legatee substituted in the said will to whom administration was granted...” in London on 5 April 1826.

My document on the Gregory Family of Watchmakers. Gregory Watchmakers in Basingstoke^J England

William Gregory

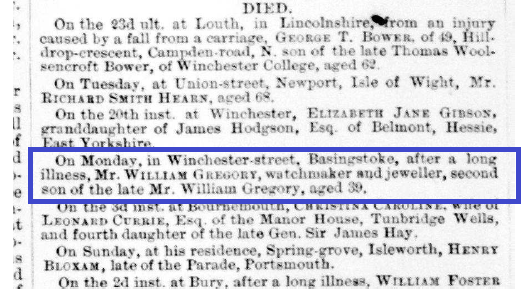

HERE was the door that frustrated my efforts for a few weeks. I’ll start by saying that in the mud of SO many people in the county with the name Gregory and SO many Williams, it was like picking the correct penguin from a colony; hyperbole this might be, but it was confusing that some people having done their genealogies seemed to, as I would later learn, crammed as many as 3 or 4 William Gregorys into a single person. But the next big break came with the following obit, published in The Hampshire Chronicle, Southampton and Isle of Wight Courier, 10 Dec. 1870…

With James’ will and this obit above, I saw the key to understanding the family line, in as it related to my project. I could now build upon William, nephew to James, and what would become the family line of Gregory watch makers.

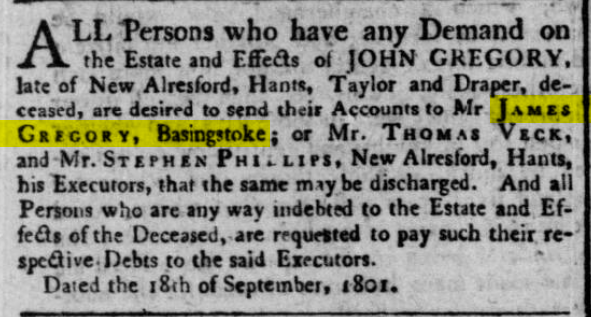

Cambridge University Press & Assessment suggests that the average age of a youngster going into apprenticeship in the early 19th century was about 15 and a half years. James’ brother John appears to have moved to (New) Alresford, there becoming a tailor and draper, and marrying Hannah Morley. John died there in 1801, when his son William was 3 yrs of age.

The Hampshire Chronicle, or, Winchester, Southampton, Portsmouth and Chichester Journal. Monday, September 28, 1801. Front page.

The widow Hannah had six mouths to feed, and here James took in William to apprentice. Given the median age for this as cited above, let’s say by 1811 (per the article below), although I’d wager that it was much sooner. William may not have been the only one working in the shop for James, but it’s clear that he was the “son James never had” and inherited the house and business. Anything inscribed “Jas. Gregory” believed to be sold after his death in 1826 is most likely “stock”, sold as an item desired by the purchaser regardless of who’s name was inscribed in it; after I took over the instrument shop I run in 2017, I was still selling items for several years that had been made by my late employer until the stock ran out. The transition would have been smooth, I imagine, and William kept ties with his family in Alresford, and there he courted and married Mary Skinner, bringing her to Basingstoke. They raised three children, one of whom was William Jr, who would also learn the trade and take over the business upon his father’s death in 1860. William Jr married Sarah Ann Penton in 1855, and she might have been the “business acumen”, seemingly carrying on the business on William Jr’s death in 1870. Sarah had learned the trade and continued the Gregory’s business as a watchmaker in her own right, training her son William Skinner Gregory. She remained in residence (5 Winchester St) until her death in 1901. Sarah Ann was buried on 16 Nov 1901 (grave G151) in Holy Ghost Cemetery in Basingstoke. (The closer St-Michael’s appears to have closed its cemetery to new burials after 1860) William S. Gregory, b. 1860, never married, but ran the business along with his sister Sarah “Annie” Ann Gregory, also never married.

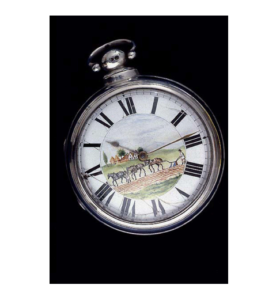

- Watch made by William Gregory, silver paired case, ploughing scene on dial, c.1842. Hampshire Cultural Trust.

- Hampshire Chronicle & Southampton Courier Winchester, Monday, March 20, 1826

Of course, the BIGGEST issue with trying to put together this family tree is that each generation of the Gregory Family seems to have a John and a Mary, as I wrote earlier. In addition to this are other Johns, Marys, Williams, and Sarahs in Basingstoke and the surrounding villages… It has been quite the slog to put together a cohesive family tree. However, I uncovered some lucky documents, the will mentioned above for James being the biggest of them all. I’ve started an Ancestry tree to attempt something of a graph to make sense of it all, and it has begun to come together. I am putting together as comprehensive a family line of the business as I can from my internet perch, and will publish it here. I hope that my work here will create a stable launching point for someone who will improve upon it and correct where new information informs.

My document on the Gregory Family of Watchmakers. Gregory Watchmakers in Basingstoke^J England

Silversmith – Watch Case Maker

Now to find out who the silversmith was who made the watch case…

- Detail of my Gregory watch.

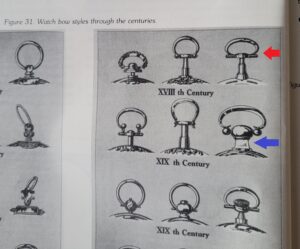

- Detail of examples from Philip Priestly’s book, showing typical examples of the stem and loop of watches for their eras.

The first image is a closeup of my Gregory watch’s stem and the second image being Priestly’s examples of stem and loop of watches in their eras. My watch would appear to have the loop not unlike one associated with the 18th century while the stem is more like what is seen in the 19th century. I may have stated that fashions never seem to shut off and on like a switch, but evolve, morph, develop… James and his watch case maker likely were slow in developing their style as trends came along, and seeing this as a link in the chain of development is interesting in of itself.

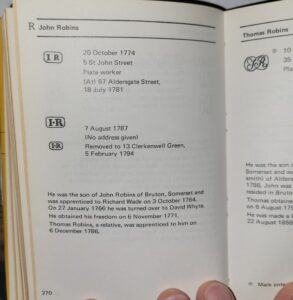

A friend, Richard Arnold, a watch repairman living just outside of Basingstoke, has corresponded with me on some of my questions. He sent me the following info and is fairly certain that my silversmith was James Richards. Given the “apprentice marks” on the inner and outer cases, the pieces were probably made by people working for Mr. Richards, under his watchful eye.

Conclusions

James Gregory was indeed a maker of watches and clocks, between 1790 and his death in 1826. He was locally known but not on a wider basis, else he would have been recognized in later books listed known watch and clock makers (he shows up in a couple, but more like a footnote). He had taken in his nephew William as an apprentice, who would inherit the business and house upon James’ death in 1826. William married and among their children was William Jr, who also learned the trade and would inherit the business. William Jr married Sarah Ann Penton who also trained in watch making; When William Jr passed, Sarah Ann continued the business, training their son William Skinner Gregory and their daughter Sarah “Annie” Ann. William S and Annie ran the business until they retired and Gregory’s shut down.

MY watch: silver, brass works, serial number 1010, with the indicated hallmarks, was made BY James Gregory in Basingstoke in 1816/17. While 1816 is “after my era”, and I have since collected some earlier watches, this one made by James Gregory has become my prized piece, my favourite. The holding of a heartbeat made by a man across the ocean and two hundred ten years before me.

Regarding the English Pocketwatch

THIS vid is worth the watching for the relevant history of watch making and this era.