UNDER CONSTRUCTION

In the thirty-five plus years of my research, as an aside of the content of letters and documents that I have handled, consulted, and even collected, I found something that I thought curious in the beginning. Instead of the commonly-expected blob of sealing wax impressed with some image or initials, I often would see the remains of a perfectly round something-or-other, sandwiched between the actual document or letter and either a back flap (for folding) or with a piece of paper clipped into a square, more or less, which was impressed atop the “round thing”. At first this seemed to be more often with official documents here in Connecticut, but as the years moved on (the 1790s into the 18-aughts), it seemed increasingly common with personal letters. There seemed to be scant little of information as to what this was and what kind of tool was used to leave on the top of the “sandwich” the series of almost pin-like impressions that almost seemed to intentionally push the top paper into that odd round-thing…

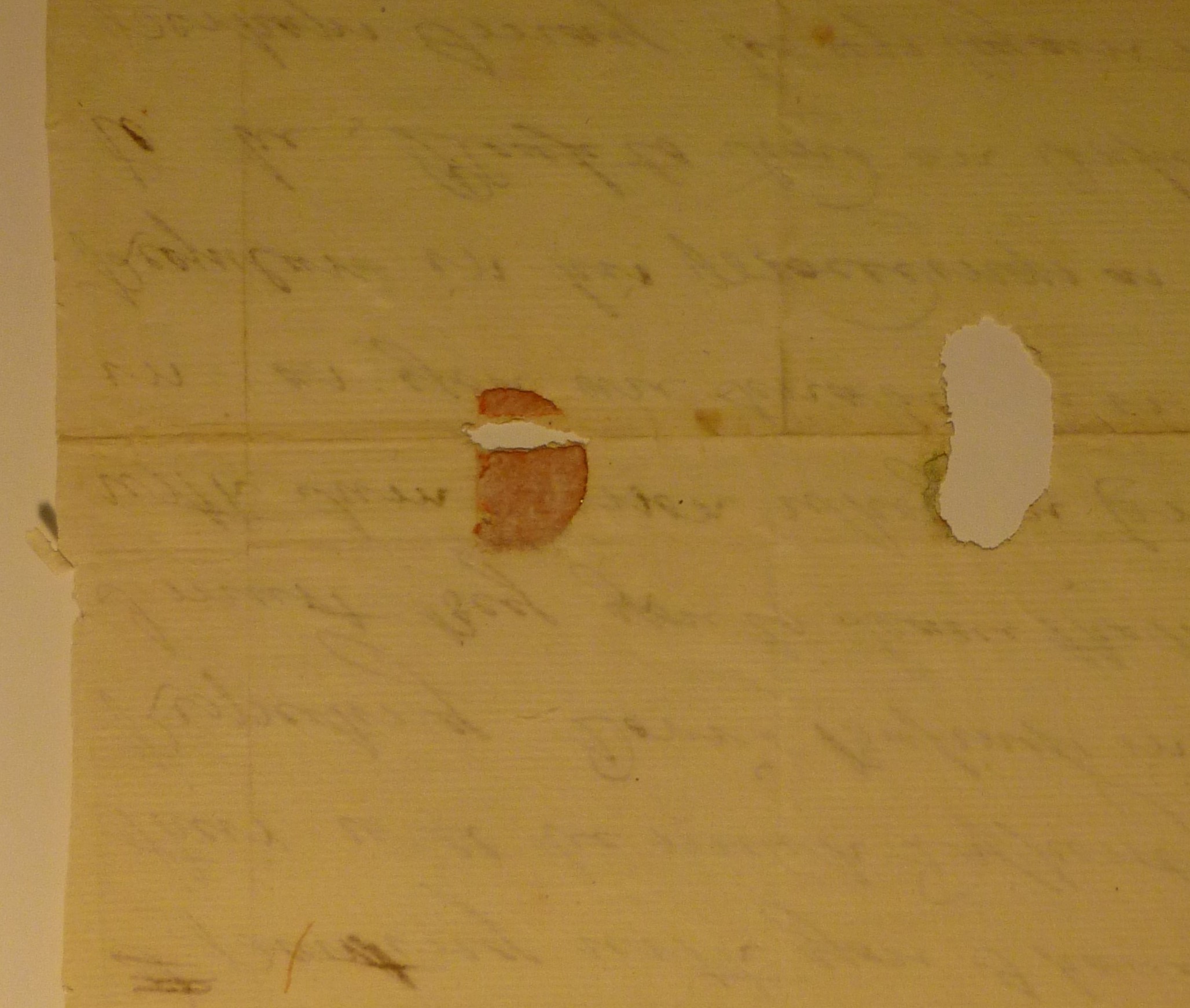

From consulting letters in the NY Public Library to the Connecticut Historical Society (now the Connecticut Museum of Culture and History), and within private collections, local historical societies, and in the dusty basements of older town hall buildings, I began to see a development in letters and how they were sent. For the Revolutionary War period, those that still had pieces of sealing wax were in keeping with our common perception of how letters were sealed before sending. Unless a scrap of paper, it was almost always a case of a large sheet folded in half, and once written upon, folded again into a rectangle roughly 3″x5″, and the outermost fold would be folded again so that the outer side and away from any writing would be sealed against the opposing side with a dollop of wax. Sometimes a seal would be pressed into the wax, showing an image or initials… More often than not, the wax would be completely between the paper and presumably pressed until it cooled and so sealed, using a thumb, perhaps, or the flat edge of something hard. When the letter was opened by the receiving party, it would typically tear a bit of the paper, leaving a small hole that could sometimes take a piece that had some of the writing upon it…

But moving beyond and into the reconstruction of the early Republic, what had been wax increasingly appeared perfectly round and made of something other than wax. The same method of pressing was employed, but not the “ooze” into imperfect blob all so indicative of sealing wax utilized with purpose rather than artistic statement.